Project conclusion and summary of outputs

BACKGROUND

In May 2011 following a generous grant by the Leverhulme Trust, the ARCdoc team (led by the University of Sunderland and in collaboration with the Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, the University of Hull and the UK Met Office, Hadley Centre) set out clarify and enhance our knowledge of climate change in the Arctic region using historical marine meteorological observations made on board Royal Navy, whaling and commercial (The Hudson’s Bay Company) ships, between 1750 and 1850.

The project was prompted by the growing need for a finer understanding of the nature of climate change in the Arctic region, particularly in the decades before anthropogenic greenhouse gases began to exercise an appreciable control on the planet. At the same time it drew upon the growing appreciation of ships’ logbooks in the provision of daily and detailed weather data from the years before instrumental observations formed part of the evidence base for such studies.

OBJECTIVES

- To identify the full range of UK-based documentary and old instrumental sources for the Arctic region.

All such UK sources have been identified.

- To abstract the written, non-instrumental and early instrumental data, calibrate and verify them for inclusion in a structured and interrogatable database.

The narrative, non-instrumental, data have been abstracted and calibrated, and a database and website prepared for its dissemination.

- To develop and improve methods for working with historical data and narrative accounts and expressing them in forms that lend themselves to scientific analysis.

New methods have been developed for treating, correcting and presenting the data.

- To use the outputs from objective 2 to provide an improved picture of climate (temperatures, wind circulations and ice coverage) during a key period in recent climatic history and to set those findings against the current understanding of conditions at the time.

For the first time a detailed picture has been re-created of Arctic climate and ice cover for the period 1750 to 1850, the data being expressed in index and quantified form.

SOURCE MATERIAL

The source material consisted exclusively of ships’ logbooks, principally in two forms; those of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) and of the UK whaling enterprises. The former are held in the National Archives in Kew, the latter are scattered around the country but the largest and most important collection is found in the Hull History Centre.

All narrative accounts from some 150 logbooks were transcribed manually by the team, and then, once in ‘digital’ form, were processed to express the descriptions in terms of indices and numerical values. This task proved demanding of time as no OCR system could be used in the process.

CONCLUSIONS AND ACHIEVEMENTS

Data abstraction: this remains a ‘manual’ task but, such limitations notwithstanding, the team have abstracted meteorological data from over 150 logbooks for the period and region in question. This notable exercise represents the complete abstraction of UK whaling and HBC logbooks for the century 1750 to 1850.

Data management: whilst much work has been completed in the last decade using ships’ logbooks, this was the first attempt to use those with an Arctic provenance; as such it produced a number of developments in data management. A system for indexing sea ice was required, and particular attention had to be paid to the question of correction from magnetic to true north wind direction records. Particular problems arose with whaling logbooks and the absence of location data. The only option was to carefully reconstruct the voyages day-by-day using such evidence as the logbooks provided and working on large-scale navigational charts to plot their routes.

Data storage and retrieval: these data have been stored, and are available, in a number of sets that allow future investigators to follow the research activities in detail. This takes the form of a) the original ‘raw’ daily data as abstracted, b) the same daily data but after correction and, c) summary sheets of the monthly data aggregated from the daily observations.

All project data is freely available on the website:(http://www.hull.ac.uk/mhsc/ARCDOC/). These consist of wind circulation and intensity indices of a form already in widespread use but, and importantly, added to these are:

- sea ice and iceberg indices

- weather indices (for rain, snow and fog)

The HBC logbooks provide a near-continuous series for the study period, from which decadal changes in climate can, for the first time in his region be obtained. The whaling logbooks are more scarce and cannot yield the same continuity of evidence. They do however provide detailed and unique observations on ice cover, and penetrated into latitudes not frequented by any other vessels.

PUBLICATIONS

Ward, C. and Wheeler, D. (2011) Hudson’s Bay Company ship’s logbooks: a source of far North Atlantic weather data. Polar Record doi:10.1017/S0032247411000106 – This paper focuses specifically on those logbooks kept on board Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) ships on their regular annual voyages between the UK and Hudson’s Bay between 1760 and 1850. The style and form of presentation of the logbooks is reviewed and particularly those aspects that deal with the daily meteorological information they contain.

Ayre, M., Nicholls, J., Ward, C. and Wheeler, D. (2015), Ships’ logbooks from the Arctic in the pre-instrumental period. Geoscience Data Journal. doi: 10.1002/gdj3.27 – This paper describes the UK sources of data, their locations, the nature of the raw data and how they may be treated and expressed in a form that renders them appropriate for scientific analysis. Discussion also takes place of the database where the original and derived data can now be found and are freely available.

Encounters with the Nantucket Whalers

During the mid 18th century, whilst the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) and English whalers were expanding their trade routes and fishing grounds, so too were the American whalers.

With the decline of whales off the coasts of Cape Cod and Nantucket, American whalers began to use single-masted sailing vessels called sloops to pursue the whales into deeper water. These voyages led the whalers farther out to sea and northward into the whaling grounds off Newfoundland and the coast of Labrador and into the Davis Straits, west of Greenland.

By the late 1760s, the fishery was becoming a hugely lucrative industry with the colonial fleet numbering around 350+ vessels in 1774. With such a large number of whalers operating at this time, it is not surprising that we find reference to these whalers in the logbooks of the HBC.

The extent of the operation in 1770, is remarked upon by Joseph Richards, Master of the Prince Rupert III in his log book on the 24th July:

‘Saw something NWbW of us which we took for a boat but as we drew nearer to it found it a dead whale. Saw a sail of sloops and schooners. At 5 the Commodore got the fish alongside and prepared for flinching it. Sent my boats and some hands to assist them, as did Captain Christopher. Handed out sails and made a rope fast to the Commodore. At 7 they began to bring blubber on board which we cut into small pieces and put into casks.’

‘At 7 spoke the schooner Roebuck, Timothy Coleman Master, 1 fish. The sloop Liberty, Joseph Coleman Master, no fish…. and the sloop Enterprize, Nathan Vaughn, two fish, all belonging to Nantucket on the whale fishery, here about being part of 115 sails fitted out from that single place this year.’

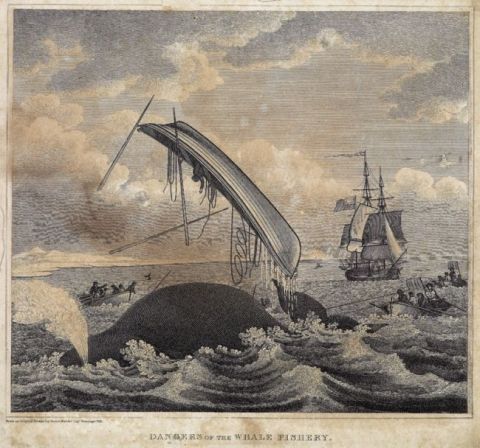

Whilst a highly lucrative business, whaling was also a dangerous enterprise. Ships operating in the icy waters of the Davis Straits or in Baffin Bay were at constant risk of being crushed by ice. The process of capturing a whale was also a fraught with danger, with whale boats often upturned or crew injured by the thrashing of the whale when it was harpooned.

Joseph Richards, Master of the Prince Rupert III tells us of just such an instance in his logbook on 28th July 1769:

‘Saw the sloop and schooner ahead of us. Sent our boat on board the schooner being the Duke belonging to Boston, Christopher Kirk, Master had been 11 weeks from Nantucket and 3 weeks in company with the sloop, Mary, between this and 62.30N and much the same longitude they had killed 10 whales. 4 black and 6 Spermaceta. The last was a black. One killed yesterday noon Captain Kirk told us that as the Mary’s boat the other day was fast to the Spermaceta whale it stove them and the fish immediately made at the mate and caught him in her mouth and held him for 2 minutes but on Captain Kirk’s boat coming up it quitted its hold and they saved the man with no other damage than her leaving the mark of her teeth in his shoulder and thigh. They likewise saved all the boats crew and killed the fish, a poor return for its kindness’.

Sadly, very few American whaling logbooks survive for the 18th century and thus these first hand references to individual whaling ships and their masters can be deemed particularly useful in giving us some small insight into the industry at that time.

ARCdoc will once again be taking to the seas, this time in the interests of education. In partnership with the Ocean Youth Trust North (OYTN) and Burnside Business & Enterprise College (based in North Shields) we will be retracing the first leg of a 19th century Arctic whaling voyage.

All of the whaling logbooks being used by ARCdoc originate from ships sailing from the UK’s east coast. Between 1750 – 1850 all east coast ports were involved with the whaling trade in some capacity. These east coast whalers would sail north to the Orkney or Shetland Islands, where they would embark the majority of their crew before heading to the Arctic whaling grounds. It is this first leg, from Newcastle to Kirkwall, Orkney that we will be recreating in a few days time!

Matthew, ARCdoc’s research student will be joining 10 students and 2 teachers from Burnside School on board the OYTN’s vessel, the ‘James Cook’, a 70ft, 54 tonne steel hulled ketch. The OYTN is a charity specialising in the personal development of young people and adults through the medium of ocean sailing.

On board the students will be keeping a replica 19th century logbook, just like the ones used in ARCdoc’s research. Using the nautical day, starting at noon, they will be keeping 2 hourly observations of the course and speed of the ship, wind direction, wind force and prevailing weather conditions. Wind and weather observations will be conducted using non-instrumental observations and speed will be calculated using a replica chip log.

Log extract from the Hull whaler ‘Laurel’ 1827

The chip log was the original device used to measure a ship’s speed, and dates back to the 15th century. The end of the log was lowered into the water, then the line was allowed to play out for 30 seconds after which the line was pulled in and the number of knots counted. Older chip logs had knots tied at every 42 feet, each knot representing 1 nautical mile an hour (or knot as it is now known). Later refinements in the distance of a nautical mile caused the knots to be tied slightly further apart at 47 feet 3 inches. It is this corrected unit of measure that is used on the chip log we will be using.

The chip log the students will be using to measure the speed of the James Cook.

Using these observations the students will be trying their hand at simple dead reckoning navigation and comparing their observations against the electronic navigational equipment (GPS) on board. It will be interesting to get a sense of the accumulated errors associated with dead reckoning.

We hope this adventure will provide the students with a real sense of their cultural history. As with many historic ports, some of the students could well be distant relatives of old Arctic whalers. We also hope they will gain an understanding of ARCdoc’s research, the sources we use and how they can be used to understand past climates.

You can follow our voyage via the OYTN’s website: http://www.sailjamescook.com/about/james-cook/follow-james-cook

We will be departing the Tyne on Saturday 20th July.

The Greenlanders – Arctic whaleships and whalers

A fascinating and very relevant talk on Arctic whaling was given by Dr Bernard Stonehouse back in October 2012 as part of the Gresham College talks at the Museum of London. He tells of the ships, the men, and the profits and losses of a long-forgotten industry.

Overview

From 1750 to the early 20th century, fleets of ‘Greenlanders’ – specially strengthened sailing ships – headed north each spring from Britain to the ice-filled Arctic seas between Canada, Greenland and Spitsbergen. Their business was whaling, their purpose to bring home oil and whalebone – raw materials for Britain’s growing industries. Arctic whaling involved more than 9000 voyages from 35 British ports: Rotherhith’s ‘Greenland Dock’ is a reminder that London was a prominent whaling port. Each voyage involved dangers unique to the trade, demanding extraordinary measures of skills and seamanship.

The presentation together with a transcript of the talk is available on the Gresham college website.

The Palmer whaling logbook collection 1820-1833

The team have recently completed the transcription of weather and ice observations recorded in a special collection of logbooks kept by Captain George Palmer (1789-1866) on board the Hull whaling ship, the Cove. This complete run of log-books written between 1820 and 1833 describe the hazards and routines of Arctic whaling at a time when depleting whale stocks in Greenland led to a search for new whaling grounds in the icy Davis Straits and Baffin Bay.

The Northern Whale Fishery; the Swan and Isabella – John Ward

Hazards of ice

The logs follow a similar format to those of the Hudson’s Bay Company and other whaling logs and contain positional information (latitude and occasionally longitude), together with observations of wind force, wind direction and weather. The state of the ice is described on a daily basis, the frequency of which is not surprising given the dangers of sailing in such inhospitable waters. On several occasions in the logs Palmer reports hearing news of whaling ships lost to the ice: On the 9th September 1825, Palmer, having spoken with the Juno of Leith, writes “we were informed of the loss of the Success of Leith and the Lively of Berwick by the pressure of the floes of ice”.

On the 3rd September 1830 Palmer reports “Spoke the Ingria of Hull who gave an account of the Achilles, Progress, Baffin and Rattles lost” and a few days later “Fairy of Dundee gave an account of the Spencer lost” (In fact, this turned out to be the most disastrous season with 19 British whaling ships lost in Melville Bay as they waited for ice to move, so that they might push west)

The Cove itself did not escape bad fortune either for on the 7th September 1829 Palmer writes “One of the men James Watson unfortunately fell with the ice the others escaped by catching hold of each other. All hands was called immediately to their assistance but before any person could get to him he sunk amongst the broken ice to rise no more”

Intrigue!

An unfortunate incident occurs on the Cove’s return voyage to Hull in 1828. Palmer notes in his log on the 13th September 1828 “John Scott an Orkneyman died after a short illness” and was buried a few days later on Cape Searle. Whilst this is not unusual, the plot thickens as we later read on the 12th October as the ship arrives into Stromness, “ A Mr Patterson, constable of Stromness, came on board on with a warrant from the Sheriff of Orkney to take James Mays charged with having killed John Scott on board the ship Cove in Davis Straits. The search made for him proved fruitless though assisted by the ships company. At 4pm called all hands aft and the Captain asked the Crew if any of them the least knowledge of James Mayes being on board the ship which they all denied. This transaction was performed in the presence of different witnesses.”

A survey of contemporary newspapers does not shed any further light on this alleged crime and thus remains a mystery, for now!

Life as a whaler was undoubtedly a hard one and whilst there was no mention of the ‘murder’ in 1828, a rather nice insight into happier times is reported earlier in the year in the local newspaper, the Hull packet on 11th March:

“On Tuesday night, Captain Palmer entertained a large party of friends on board his ship, the Cove whaler, in Shields harbour. A great portion of the deck was covered in for the purpose of dancing, which spritely amusement was entered into with the utmost spirit and vivacity. At 12 o’clock the whole party retired to the supper table, which was laid out between decks in a style of elegance quite unparalleled, consisting of every delicacy to please the eye or gratify the palate of the most fastidious. After supper, a humourous and characteristic song, written for the occasion, was sung with great applause. At two, the dance was resumed, and kept up with undiminished spirit until 5 o’clock, when the company returned on shore, highly gratified with the night’s amusement, the hearty welcome of Captain Palmer, and the elegant attentions of his amiable wife”.

The ARCdoc team are extremely grateful to the family of George Palmer, the Scott Polar Research Institute and Bernard Stonehouse for making copies of these logs available to the team.

ARCdoc in the Arctic – final review

Our intrepid Arctic explorer, Matthew Ayre, has now returned from a profitable and enjoyable cruise in Arctic waters. Here is his review of his time in the frozen North.

Waiting in the departure lounge of Anchorage Airport, I was unknowingly about to learn first rule of travel in the Arctic: do not expect things to happen on schedule! I boarded my flight bound for Barrow, via Fairbanks and Deadhorse (yes, that’s the name!), still yet to make contact with any of my future crewmembers. Everything was fine until we reached Fairbanks “Sorry folks, runway is fogged out at both Deadhorse and Barrow”. Four hours later I was still in Fairbanks, still too foggy to continue further north and my flight was redirected back to Anchorage. Ushered onto a larger plane bound for Deadhorse, I departed Anchorage for the second time that day. Thankfully the fog had lifted by the time we landed at Deadhorse, only for a mechanical problem to ground the plane for a further 3 hours! Eventually I was flying west towards Barrow along the coast of Alaska’s North Slope, peppered with thousands of shallow lakes and rivers it was stunning view, finally landing in Barrow a mere 12 hours later that expected.

Once in Barrow I met up with the Healy’s science party and taken to the NARL (National Arctic Research Lab) huts where we would be staying. We had some time to look around Barrow before flying out to meet the Healy. At first Barrow seemed a barren and uninviting place, foggy and desolate but I soon came to change my views. With a rich cultural history, fascinating relationship with science and friendly local population I really enjoyed my short time there and hope to return one day.

A short but exciting helicopter ride later I was finally aboard the Healy, issued with a pager so I could be contacted by anyone onboard and shown my room. I ended up sharing with Chad and Ben, both National Ice Centre observers who I would be working closely with over the next five weeks.

The Healy headed due north once everyone was aboard, the fog once again causing some delay. Within 48 hours I saw my first piece of ice! A large piece of melting multi-year, time to start my observations!

In order for my experiment to work I need to get sets of parallel observations, one using the historic terms and one using the modern. Chad and Ben from the NIC would be making the modern observations and I would be making observations using the terms defined by William Scoresby Junior in 1821. It was agreed observations would start at 10am and be taken every 2 hours up till 8pm. Alongside the actual ice observation, position, wind direction and wind speed would be recorded.

Everyone aboard was assigned a watch, to monitor the multi beam sonar that was being used to map the sea floor. I got lucky and my watch 12pm to 6pm, there being 4 of us on watch I was still able to complete my ice observations.

I had a couple of preconceptions about the sea ice before I had actually seen it. First I presumed being there in the end of summer all I would see was ice in various stages of melting and secondly that ice the was relatively static. In reality the ice is extremely dynamic, constantly being moved by the wind. Also we saw all stages of ice development, from newly freezing grease and nilas ice to rotten ice.

I had been worried I may not see any ice at all! This year saw a new record low sea ice minimum in the Arctic, with a large storm melting a lot of ice before I’d left even left the UK. Thankfully I saw much ice, despite getting as far north as 84N we were almost constantly in the Marginal Ice Zone. This was good for my observations as this is where the whalers hunted, but it is not good for the Arctic in general as at that latitude is usually solid pack ice.

The highlight of the cruise, apart from getting a lot of good data, was seeing five polar bears, including a mother and cub! It’s amazing to see them in their natural habitat out on the sea ice, hundreds of miles from any land.

We didn’t see any whales up in the ice but were treated to a few sightings when travelling south through the Bering Strait to Dutch Harbour, Unalaska, where I was to leave the Healy.

It was truly an amazing experience that as forwarded no end my understanding of sea ice and the conditions the whalers worked.

I would like to thank Professor Larry Mayer from University of New Hampshire for letting me aboard, Jack Wolskin York for providing me with the gear to keep warm up there and finally the crew of the Healy for ensuring a safe and successful cruise for all aboard.

I wasn’t aware there was a blog of the cruise until I was in it! So here is a slightly belated link to everything that was going on:http://ccom.unh.edu/healy-12-02-research-cruise

ARCdoc in the Arctic

The ARCdoc PhD student, Matthew Ayre, is now working in the Arctic region. Here are his first-hand reports:

Wed. 22nd August 2012

Firstly I apologise there has been no mention of the following on the blog until now: confirmation of this trip was quite last minute.

I am currently somewhere over the Davis Straits at 35,000 feet or so on my way to Barrow, Alaska where I will be joining the US Coastguard’s flagship icebreaker research vessel; the Healy. The Healy will be sailing north from Barrow, its primary research mission being to survey the extended continental shelf and will then return through the Bering Sea to Dutch Harbour in the Aleutian Islands. The five-week cruise is being lead by Professor Larry Mayer of the University of New Hampshire and is due to sail to higher latitudes than any other international Arctic research cruise this year.

I am joining the cruise in search of sea ice. The ships’ logbooks ARCdoc is working with contain, as you might expect, recordings of sea ice. However it wasn’t until the data abstraction was well underway that we realised how detailed the descriptions of ice actually were. The most detailed ice observations are found in the whaling logbooks. The whaling ships actively sort out the ice edge as this is habitat of their prize, the majestic bowhead whale (Baleana mysticetus). Subsequently they stayed alongside the ice, following it North as the summer months proceeded (the whaling season generally lasted from March until September). Their logbooks have many observations of ice conditions at the time that can help us understand the position of the sea ice edge, the rate and distance it melted back and what kind of ice was present in the Marginal Ice Zone (the area between solid, continuous sea ice cover and open water). While there is no international agreement on how to measure the edge of the sea ice, it is generally accepted that it is the area of 15% ice coverage in the Marginal Ice Zone.

The whaling logbooks contain ~22 individual terms to describe the ice. The terminology is consistent across all the logbooks and appears to have already been established and in common use before Britain re-entered the Arctic whaling trade in 1750.

The key to utilising these terms in climate reconstruction lies in discover what they tell us about the ice. Thankfully William Scoresby Jnr, the famous whaler and scientist from Whitby, had the foresight to publish definitions for many (18) of these terms in his book ‘An Account of the Arctic regions, and a description of the northern whale fishery‘.

Many of the terms Scoresby recorded are still in use today, but they do not necessarily have the same meaning.

In order to unlock the true meanings of the ice terms found within the logbooks, ARCdoc are developing a sea ice dictionary. This will link historical ice terms with their modern counterparts allowing the direct comparison of historic ice data to modern and future ice conditions.

The ensure the accuracy of the dictionary all ice terms (published in Britain) have been sourced, from the earliest (Scoresby 1821) to the most recent (Marine Observers Handbook 11.ed 1995) and the evolution of each term tracked. The reason I am joining the Healy‘s cruise is to test the accuracy of the dictionary using parallel field observations of current sea ice conditions, using the oldest and newest terminology. The cruise may also help unlock the meanings behind the few ice terms Scoresby did not define in 1821 that are in common use throughout the logbooks.

The fact I am joining this cruise is still a little surreal. To experience the environment the whalers visited annually will give a whole new dimension and appreciation to the information in the logbooks.

I would like to extend a special thanks firstly to Professor Mayer for kindly letting me join his cruise, to Neil and Tim at the Jack Wolfskin store in York, UK for their technical expertise and support in preparation for this trip. Also the support the Leverhulme Trust and the University of Sunderland, without whom this would not be possible.

I intent to try to update this blog at least once while aboard and if possible update twitter on the cruise’s progress, although there is no guarantee I will be able to do this as internet connection aboard is intermittent and limited.

Twitter: Made_by_Matt

Lets hope I see some ice!

Matt

Here I am trying out my winter gear courtesy of Jack Wolfskin

RGS-IBG Annual Conference 2012

This year’s RGS-IBG conference was held a Edinburgh University from 3rd – 5th July and packed in a massive 279 sessions!

I came up to Edinburgh on the 2nd as the RGS-IBG Post-graduate forum held a training day. The day itself was very useful, dispelling myths on what a viva actually entails and suggesting career options after PhD. It was also great to meet up with friends made at previous conferences, to see how everyone was getting on with their research and of course, network and meet new people. The Post-graduate forum was well represented through-out the main conference programme with several sessions on ‘New and emerging themes in post graduate geography’ and a new trail session on ‘Challenges and connections in your research’; the latter of which I presented in. It was an interesting session as although aimed primarily at post graduate researchers, it was well attended by seasoned academics. The session took the form of a round table discussion and then a series of focus groups based around the emerging themes. The session continued into the pub and I certainly found it very useful to get fresh opinions and methodologies from others who are in totally different research areas.

It was good to see documentary climatology represented in the form of Alex Berland’s (University of Nottingham) PhD research on the climate history of Antigua. His paper, titled ‘”Another visitation of elementary strife”: climate and crisis in a colonial Antigua’ focussed on the occurrence of extreme weather events, namely drought and/or hurricanes that had massive impacts on the islands population at the time and some of his early results show a close correlation between extended periods of extreme climatic conditions and civil crisis. His research is archive based and draws on a number of sources including government records, plantation papers and missionary correspondence.

Alex’s abstract can be found below, along with other papers presented during the session. Unfortunately George Adamson (University of Brighton) was unable to make the conference which was a pity as I was looking forward to hearing his presentation.

While in Edinburgh I took the time to have a search of the archives held in the National Library of Scotland and National Museum of Scotland. William Scoresby Jnr (Whitby whaling captain and scientist) went to university in Edinburgh and was later made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. While there was no manuscripts belonging to/or relating to Scoresby, the library held Sir John Franklin’s original field diary from 1821 when he and his crew became trapped in the ice while searching for the fabled North West Passage. The diary is written in pencil and very faint. A lot of it is indecipherable but the sections that are legible give an air of grave concern regarding the situation with many of the crew not surviving the perilous conditions. A fascinating document of a national hero which gives a truely personal insight into the human endeavour of the sailors who entered this region.

The conference was so well organised and fluid it was hard to tell it was as big as it was. Thanks to RGS-IBG and Edinburgh University for a very interesting and enjoyable few days….see you RGS-IBG ac2013!

Matt

More information on this conference and the full program can be found here:

http://www.rgs.org/WhatsOn/ConferencesAndSeminars/Annual+International+Conference/Annual+international+conference.htm

A strange sail in the NE quarter…

ARCdoc is drawing on a number of sources to build up a picture of the climate of the far North Atlantic and the Arctic. The focus to date has been on transcribing weather observations from logbooks kept by the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) and whaling ships, with a view to turning our attention to the Royal Navy discovery ships’ logbooks, once this is complete.

When you are working on a particular source it is easy to think of those particular ships operating in isolation, but in fact the HBC, whalers and Royal Navy were all operating in similar areas at one time or another and on occasion, they did ‘bump’ into one another.

It is rather helpful when this occurs because this offers us the chance to compare their encounters. A rather nice illustration of this occurs in July 1821 when HBC ships the Prince of Wales and Eddystone, together with the Lord Wellington (transporting settlers) meet with the discovery ships HMS Hecla and Fury in the Davis Straits, off Resolution Island.

From the Prince of Wales logbook:

13th July 1821 “at 8 two ships in sight from the mast head WSW off us 12 or 14 miles appearing to be grappling which we take to be the discovery ships”.

16th July 1821 “the discovery ships grapple near us and Captain Parry sent his boat for me to go on board the Fury”

From the logbook kept on board HMS Fury:

14th July 1821: “At noon strangers ENE 7 or 8 miles”

16th July 1821: “At 8 moderate and cloudy, 3 strangers and Hecla close to. Hauled sails. Sent letters on board the Prince of Wales for England. Captain Davidson of that ship came on board”.

As well as the logbook observations, many of the Captains of the discovery ships later recounted their adventures in printed narrative accounts. These accounts can prove useful in providing more detailed information about the encounter, as we see in Parry’s description of their ships meeting in his ‘Journal of a second voyage for the NW passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific, performed in the years 1821-22-23 in Hecla under the orders of Captain William Edward Parry RN,FRS and commander of the expedition’ London: 1824

The Meeting of the Hudson’s Bay Company Ships Prince of Wales and Eddystone with Captain W.E. Parry’s Ships Hecla and Fury

16th July 1821: “The ice being rather less close on the morning of the 16th, we made sail to the westward, at 7:45 am and continued ‘boring’ in that direction the whole day, which enabled us to join the three strange ships. They proved to be, as we supposed, the Prince of Wales, Eddystone and Lord Wellington, bound to Hudson’s Bay. I sent a boat to the former, to request Mr Davidson, the master, to come on board, which he immediately did. From him we learned that the Lord Wellington, having on board one hundred and sixty settlers for the Red River, principally foreigners, of both sexes and every age, had now been twenty days among the ice, and had drifted in various direction at no small risk to the ship. Mr Davidson considered he had arrived here rather too early for advancing to the westward, and strongly insisted on the necessity of first getting to the northward, or in-shore, before we could hope to make any progress; a measure, the expediency of which is well known to all those accustomed to the navigation of icy seas”.

Mr Davidson’s comment that he “considered they had arrived too early for advancing westward” is an interesting and useful one as it shows us how familiar the HBC master’s were with the environment they operated in and in particular, their knowledge of the timing and extent of sea ice in the Davis Straits.

When we come to the analysis stage of the project, combining the data from the ships’ logbooks with secondary sources such as the one above, will undoubtedly provide us with a richer picture of the weather conditions and presence of ice experienced on those voyages.

Visualising ships’ logbook data

Today I came across some great work done by Ben Schmidt who has taken positional data from ships’ logbooks and visualised them to show the voyages of British, Dutch, Spanish and other ships over a period of 100 years (1750-1850).

This visualisation uses positional data which were transcribed as part of the CLIWOC project back in 2001-2003 and include data from the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) logbooks, a source we are continuing to work with as part of ARCdoc project.

In this visualisation you will see that the HBC ships start to appear from 1760 (further data are available and being transcribed as part of ARCdoc) travelling from the UK over to Hudson’s Bay.

Two interesting points to note are the small seasonal window in which these ships operated as they left the UK in June and returned in September or October in order to avoid the worst of the ice in the David Straits and the Bay and that although generally they would voyage north from the Thames up to the Orkney’s before heading west to Hudson’s Bay they would, on occasion, take a southerly route though the English Channel.

Visualisations such as the one above are an extremely useful tool for us, for several reasons:

- Quality control: they can show us where there are errors in the data. For example where positional data is plainly incorrect, e.g. a ship voyaging on land!

- Analysis: The ship’s progress in time and space and any instrumental observations recorded on board can be compared against various modern climatologies such as wind direction and strength, temperature, air pressure and extent and timing of sea ice.

A nice example of the latter is this visualisation created by one of the ARCdoc team Philip Brohan which shows the progress of HMS Hecla on its voyage to the Arctic in search of a NW passage from 1819-1820 with modern climatolological sea surface temperatures (SST) and sea-ice overlain:

As we collect more data we hope to make more visualisations, and in particular, it will be interesting to see the whaling logbooks represented.